Brain Maps Hint at Response to Music

Katherine Wright – April 2, 2020

Originally published by Physics 13, 50: https://physics.aps.org/articles/v13/50

Playing unfamiliar music to patients could improve music therapy outcomes.

Music can promote brain healing, but scientists are still trying to understand which types of music work best for each patient.

When Melia Bonomo wants to kick back and relax, she turns to music and the gentle melodies of pop star Ed Sheeran. Like many people, the physicist feels her mood lift with certain tunes, a change doctors exploit to improve the health of patients with cognitive impairments. But some patients are unresponsive to music therapy. And it remains unclear exactly what restorative changes music actually induces in the brain. New results from Bonomo, a graduate student at Rice University, Texas, and her colleagues suggest that clues to both of these problems lie in how the brain responds to a listener’s favorite tune. Bonomo was set to share her findings in a session on the physics of the brain at the March Meeting of the American Physical Society earlier last month. (The meeting was canceled due to concerns about the new coronavirus disease, COVID-19, but Physics is reporting on some of the results that would have been presented.)

“Music therapy doesn’t work for everybody,” says Bonomo, who collaborated with researchers at Houston Methodist Hospital’s Center for Performing Arts Medicine. “We wanted to see if we could better understand why that is from how a person’s brain processes music.”

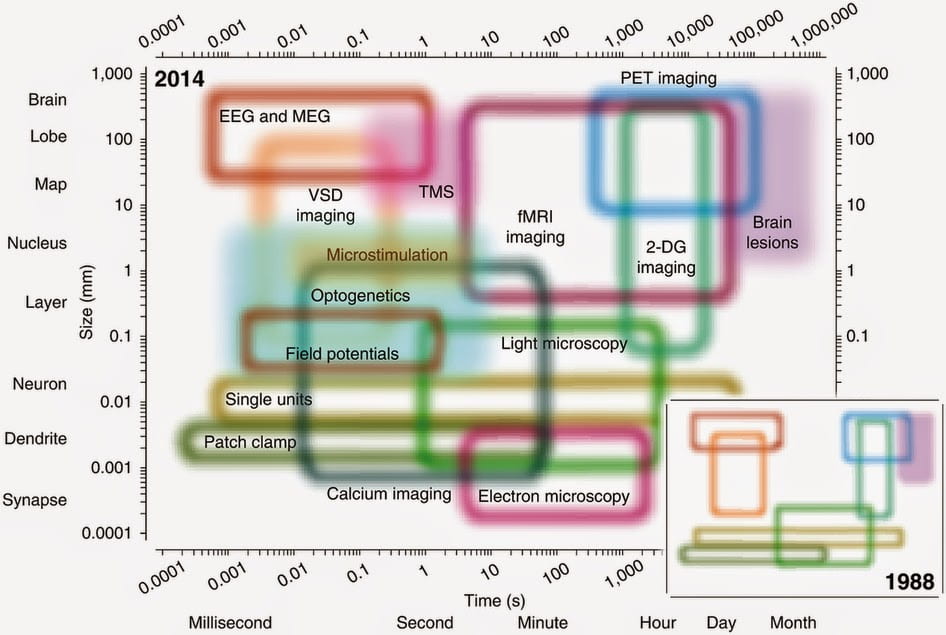

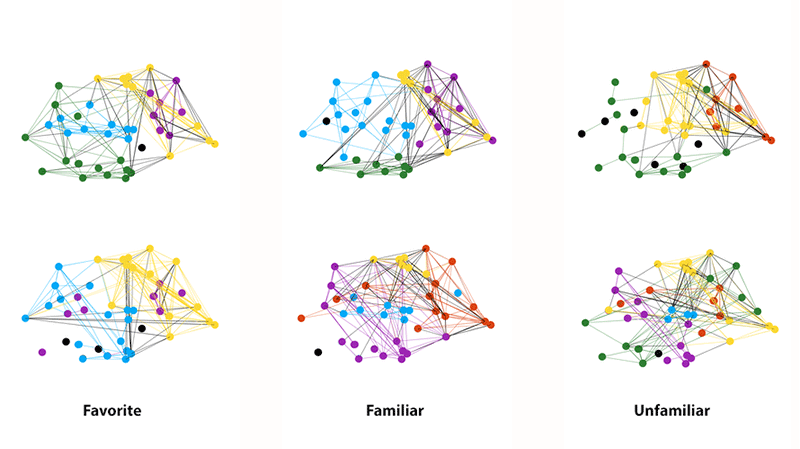

In the study, Bonomo and her colleagues used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to monitor the neuronal activity of 25 people as they listened to six audio excerpts. Each person’s set list included their favorite song, a Bach concerto, and an old newscast by Walter Cronkite. The team then translated the resulting fMRI images into network-like maps, with one map for each excerpt per person. To make these maps, the researchers divided the brain into 84 regions and drew a connecting line between two regions if they had similar patterns of activity during an audio excerpt.

Bonomo looked first at the brain maps of participants listening to their favorite songs. Within these networks, she noticed that some regions were more strongly connected with each other than others, forming a “community.” She then found that the networks fell into two categories: those where there were many connections between different communities and those where there were fewer. And interestingly, the category for a participant’s map was predictive of how they would respond to the other five sound clips.

She and her colleagues found that when a participant’s “favorite-song” network had many intercommunity connections but few intracommunity ones, the distribution of connections changed significantly for each of the other excerpts. But when the opposite was true, these connections tended to stay in place, unless the participant was listening to the most unfamiliar sound clips. (For the people in the study, the least known excerpts were a melody from a Japanese opera and a passage of foreign language speech.)

The fact that networks with more isolated communities are harder to disrupt is well known in network theory, explains Bonomo. Seeing this effect in the brain’s response to music tells us that, for some, forming new neuronal connections—something the brain needs to do to compensate for an injury, for example—may require a bigger auditory stimulus. That could have implications for music therapy, where clinicians select music to foster neuronal connections and help the brain heal. Typically, therapists select popular melodies, such as the classical music of Bach or Beethoven, to stimulate a recovery. But the new study suggests that those pieces might not be the right ones to play for everyone, says Bonomo. Instead, unfamiliar music might be the best bet. Bonomo and her colleagues are currently testing this hypothesis in a study of people with mild cognitive impairment.

Although Bonomo’s work went unpresented at the March Meeting, she did share it on Twitter. Inspired by fellow physicist Douglas Holmes of Boston University, she condensed her planned talk into ten slides that she tweeted out under the hashtag #APS10slides10tweets. She hopes that the tweets will scroll across the screens of others studying how music impacts the brain. While she doesn’t know yet if that has happened, she said that sending the tweets “was a cool way to publicly share a snapshot of my research.”