Our “Tools of the Trade” series in Archways highlights the research technology and methodologies used by the Rice ARCHES Initiative.

Modularity of the Brain

This month Fengdan Ye from the Department of Physics & Astronomy discusses an analysis method being used to study brain activity in Project CHROMA.

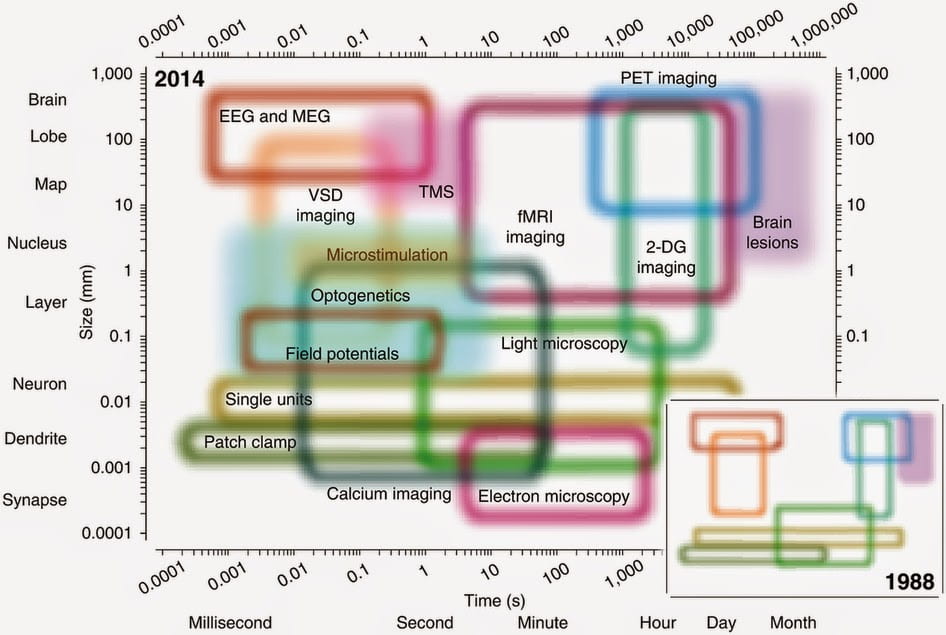

In recent years of neuroscience research, it has become more and more popular to view the whole human brain as a functional network. The structure of the human brain network has been studied in relation to cognitive performance, as well as disease progression. Modularity is one of the many ways to quantify the structure of a human brain network, and it’s a concept I have been working with throughout my PhD.

What is modularity? To understand that, we first need a clear picture of what a whole-brain network looks like. A network consists of nodes and links. In our case, the nodes are different brain regions. These regions are usually defined from existing divisions of the human brain, which can be based on either anatomical or functional features of the brain. For example, Brodmann areas are brain regions defined based on the microscopic cellular composition of the brain. The links between these regions can be defined in many different ways. One popular way is to derive the links from functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data. Specifically, the Blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) imaging method in fMRI gives information on the level of activity of any brain regions at any given time. A link exists between two brain regions, if they show synchronized activity across a period of time. A link is absent if the activity of two brain regions is not coordinated.

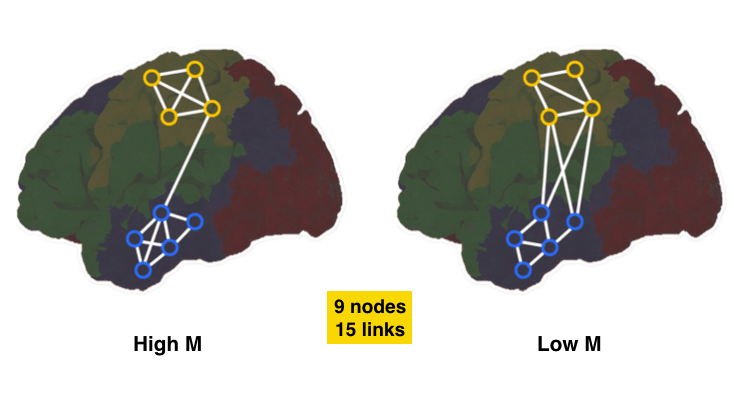

Modularity quantifies how modular the brain network is. The higher the modularity, the more modular the network is. For example, let’s assume we have six brain regions A through F. If brain regions A, B, and C are all linked to each other, and D, E and F are all linked to each other, but there is no link between the first group (ABC) and the second group (DEF), then the network is very modular. Under the context of BOLD imaging, this means the brain has two distinct functional modules: one consists of ABC and the other DEF. The regions within each module always activate together, but regions across modules do not communicate functionally. On the other hand, if there are links between all six regions, then the network is less modular because it is harder to define which regions work more closely with each other. Below is another example of low- and high-modularity networks:

In research, people not only look at the modularity value of a brain network, but also the compositions of the identified modules. This method has shed light on human cognitive and behavioral function, as well as prognosis and progression of diseases, such as stroke and Alzheimer’s disease.

For more in-depth reading:

O Sporns and RF Betzel (2016), Modular Brain Networks. Annu Rev Psychol, 67:614-640.

G Chen, HY Zhang, C Xie, G Chen, ZJ Zhang, GJ Teng, and SJ Li (2013), Modular reorganization of brain resting state networks and its independent validation in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Front Hum Neurosci, 7:456.